Sandpits are an increasingly popular choice for the distribution of Research funding by RCUK. I have just been part of an EPSRC evaluation exercise on Sandpits, so I thought I would dig some photos out of the archive and give an idea of what goes on, which I hope is helpful to those unfamiliar to this process.

I’ll deal with the application process in another blog, as it requires a different approach to conventional grant applications. My experience is with EPSRC sandpits, which are held in country hotels with large function facilities.

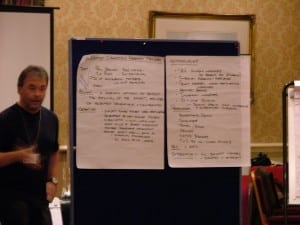

PIC1 illustrates the state of play towards the end of day 1 of the EPSRC ‘LowCarbon Airports’ Sandpit which was held towards the end of 2008. At this point, we had checked in, completed some ice-breakers, and in groups had started to brainstorm the issues associated with the theme. The yellow cards on the floor are the outputs of this process which are now being moved around and coalescing into challenges (PIC2).

The process is one of the most intensive and tiring experiences. Starting at 9.00, the activities run generally until 18.00, however that’s when the hard work really starts, with clusters working long into the night. Actually in some cases, all night!.

Be prepared to do a lot of presenting! The ideas, as they coalesce are repeatedly presented by their champions and honed by criticism (both positive and negative) from the floor. It’s at these points that clear projects and project groupings start to emerge (PIC3).

Who’s there?

There are generally three groups of attendees:

Academics who are the focus of the Sandpit

Facilitators – a professional team which runs the Sandpit and guides the process through its stages to fruition

Stakeholders – Industry and commercial interest groups are represented to maintain the applicability of the outcomes

Interestingly, in the background of PIC3 is a poster which I put up with points which are highly salient golden rules for Sandpit participants on all sides:

Stakeholders – ‘suspend disbelief’ in impracticalities

Issues – problems rather than solutions

Academics – ‘forget’ initial preferences and objectives – think outside the box

All of which is intended to facilitate the creative process. By day 3, a number of projects have started to emerge, with a core set of champions, loose ‘memberships’ and plenty of ‘floating voters’. Essentially, there is a fixed budget for each sandpit, and open competition for funding, so the process is both collaborative and highly competitive. In this case, there was a budget of £3.4M, with 10 strong contenders emerging….

Now the strategic ‘haggling’ between individuals and groups begins, as the competition increases to produce credible,fundable projects, and also to maximise individual involvement. A word of caution here is credibility. There is no difference between this part of the process and any other proposal procedure. Not only is a well thought out project plan with credible partnerships an absolute necessity, but also the crucial aspects of adventure, risk and most importantly ‘risk mitigation strategies’.

Unique to this process is that funding is allocated on the final day of the Sandpit, so all potential projects must be fully costed, with finalised members, objectives and project plans.

There is no limit to the number of projects which you can propose, or the number of projects in which you can be involved. However there is generally a strong steer from the Stakeholders as to the preferred projects and groupings as they develop. Finally, the projects are ranked in preferential order, and a steer is given as to what adjustments need to be made to costings on the individual projects.

In this Sandpit, 10 projects were proposed, with 7 being funded to a total of £3.4M. Three of the projects are currently running here at the University of Lincoln in the School of Engineering.

Most importantly, 19 out of the 22 participants came away with something to show for all the effort, ranging from studentships up to PI of large multi-centre projects.

All in all a very positive experience on the whole. In particular, the sandpit sparked multi-disciplinary, inter university collaboration which has acted as gearing for subsequent collaborative projects. all that’s left to do after the event is to make sure you get your full proposal in through the JeS system in time!

You can find out more about the funded projects via the Airport Energy Technologies Network (AETN) which is hosted in the School of Engineering at the University of Lincoln: